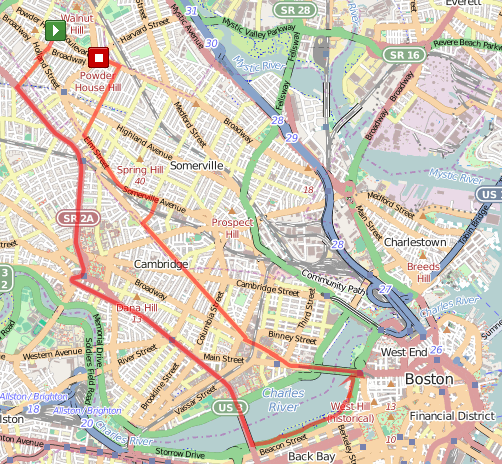

BOSTON, SOMERVILLE

August 2004 – October 2011

Once, there was a silver seashell. It lived on a sun-porch in Jamaica Plain. Often, three women would visit the silver seashell. One by one, in pairs, or all together, the women would sit. Sometimes they would talk, but not always. But they would always smoke, and then they would stab the silver seashell with burning cigarettes.

Over and over and over.

The illustrator, who loved to draw the human anatomy (especially teeth), would stab the silver seashell with American Spirits. The graphic designer and the literary critic, apparently more colonial in their tastes, stabbed it with Parliaments. The literary critic was really a graduate student learning to be a literary critic. She was home in the day quite often and terribly nervous. She stabbed the silver seashell most of all.

The seashell was large and its silvery shimmer was spray-painted. The women sat, filling it and filling it with burning cigarettes, all the year round. Even in winter, when noreasters would fill the sun-porch up to the windows with snow.

The illustrator and the graphic designer were natives of Massachusetts and had been friends since college. The literary critic was new. She’d answered their advertisement. In their initial interview, the graphic designer showed the literary critic the sun-porch and said,

“We like to come out here, smoke some butts…”

The literary critic smiled knowingly, though she thought the designer had said “buds,” and she quickly began to calculate the extent to which she cared about living with habitual drug users. In two bats of the eye she decided she didn’t. It was a huge apartment on a lovely, tree-lined cul-du-sac in a hip neighborhood. And there was this sun-porch for smoking things with people who didn’t mind if you did. Later the three women laughed together about quirky regionalisms, like “butts,” “bubbler,” and “packy,” and the zany misunderstandings they often caused.

The literary critic had been smoking cigarettes for over ten years, ever since she was fourteen years old. Back then, it was anything she could get two fingers around, but when she found a gas-station attendant willing to play dumb and take her buck-eighty, she always ordered Marlboro Lights.

“Hard pack.”

In those days, she’d walk her block, find a hiding place, smoke and feel like James Dean. Later, she’d drive around town, smoking and singing. Her favorite song to sing was the Toadies “Possum Kingdom,” and she would always belt along: “Do You Wanna Die?”

The critic, then, was seventeen. The dark humor of this scene did not strike her. At the time.

The car she had at twenty-two was old, and one day its power windows stopped rolling down. So she popped the sun roof and filled her ashtray to overflowing. All future cars, she resolved, would have the manual windows you cranked down yourself.

But that was not Boston in cigarettes. She smoked a lot in those days, but in Boston it seemed she smoked constantly.

It may have happened anyway, but two dramatic events prompted the critic to inhabit the sun porch alongside the silver seashell. She had lived in Jamaica Plain for less than a week when her grandfather passed away. She returned from whence she came. She arrived at her boyfriend’s house.

“I just said goodbye to you,” he said, failing to conceal his irritation.

Back in JP after the funeral, the boyfriend broke up with her over the phone. Both cruel and cliche. There she sat: cell phone, sun porch, cigarettes, seashell. And there she stayed, for hours and hours, smoking and crying. And once school started, on the sun porch she could study while she smoked without ceasing. Away from the sun porch, she entered into the “every fifteen minutes” phase of life.

Once she met the man who would become her husband, she tried to cool it. Fortunately for her, he was a devotee of rock clubs, and he was understanding–a lot of people he knew and liked were smokers. She almost never smoked around him. But once apart, she would return to the sun porch–six in a row for the silver seashell.

As the relationship grew more serious, she tried to cut back. Once engaged, she quit. But her arms and legs grew great rashy flames in protest. (Nicotine tricks the body. It makes the body think that without nicotine, the body can’t survive.)

Once married, the critic’s attention returned to graduate school, comprehensive exams, confusion, frustration. She began to fantasize about fancy clove cigarettes, long, sleek cigarette holders, and abalone-encrusted cigarette cases. She would peruse these fanciful products online. And then one day she bought some clove cigarettes. She started smoking again.

She lived in Somerville near Harvard now. The seashell and sun porch were long gone. She sat on the stoop and just blatantly littered the sidewalk with cigarette ends. She got to know each of her neighbors this way. A near constant presence on the stoop. Or so it must have seemed to them.

But the every-fifteen-minutes phase was long past. From the first clove cigarette, for a period of five years she tried to keep herself to under six cigarettes a day. She took up collage. She played scrabble with herself. She did a lot of online shopping. She learned that Parliaments burn too quick, leaving her wanting more. She learned that American Spirits burn far longer, and she could have just one.

In October, 2011, two days after her husband was laid off and six months before she would defend her dissertation, the critic lit a cigarette as she waited for the bus. And then she made a ludicrous decision.

“Yeah. That’s gonna be the last one.”

And, more or less, it was.

A few years back, a student had complained on a course evaluation that they’d seen her smoking before class. The critic decided to find places to smoke out of sight. Shortly before this particular October day, she’d spent about fifteen minutes looking for a solitary smoking spot. No one’s got time for that.

And then, there was the breathing. Breathing felt gray. She felt gray before, she felt grayer after, and she felt gray during, which really obviated the whole enterprise. It was like she could feel the shit killing her.

So she stopped.

— Rebecca Thorndike-Breeze